Bible - Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha

APOCRIPHA AND PSEUDOEPIGRAPHS, two groups of writings, primarily from the Second Temple, related in their themes or motifs to the Bible, but not included in the Jewish biblical canon.

The name apocrypha is applied to books that are not included in the Hebrew Bible, but are included in the biblical canon of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches. Pseudepigrapha as a whole are not canonized by any of the Christian churches; only a few of them are considered sacred by the Eastern churches (in particular, the Ethiopian). Apocrypha are mostly anonymous works of a historical-narrative and didactic nature, and pseudepigrapha are books of visions attributed to the patriarchs. The Talmud combines both apocrypha and pseudepigrapha under the title sfarim hitzoniim (סְפָרִים חִיצוֹנִיִּים, `external books`).

The number of apocrypha is strictly defined. As for the pseudepigrapha, although the early Christian authorities, the so-called church fathers, left lists containing the titles of many pseudepigraphic works, it is unlikely that the exact number of pseudepigrapha that existed during the heyday of pseudepigraphic literature will ever be known. Many pseudepigraphic works, the existence of which was previously unsuspected, were discovered in the caves of the Judean Desert (see Dead Sea Scrolls).

The apocrypha include:

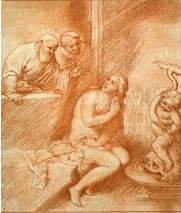

The First (Greek) Book of Ezra is a compilation of II Chronicles (chapters 35 and 37), the biblical book of Ezra and the book of Nehemiah (chapters 8–9) with the addition of the story of the contest between the youths. The book of Tobit is the story of a man from the tribe of Naphtali in Nineveh and his son. The Book of Judith tells of a brave woman who killed the enemy general Holofernes. The Wisdom of Solomon examines the fate of the righteous and the wicked. The Book of Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremiah, which are supplements to the Book of Jeremiah, condemn idolatry. The Tale of Susanna and the Elders, which is a supplement to the Book of Daniel, is the story of a righteous woman and the elders of the city who covet her. The story of Bel and the Dragon, included in the Septuagint as a further addition to Daniel, is an account of Daniel's service to Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon and Darius the Mede, and his demonstration of the futility of idolatry. The Prayer of Manasseh, attributed to King Manasseh of Judea (Manasseh, 698–643 BCE), is a prayer of repentance for sins, attributed to to this king in accordance with II Chronicles 33:11–12 and 18,19.

From a historical point of view, the most important of the apocrypha is the first book of Maccabees, a historical narrative of theHasmoneans from the revolt of Mattitias to the death of Shim‘on. The Second Book of Maccabees tells only of the wars of Jehuda Maccabee. From a literary point of view, the most outstanding apocrypha is the Wisdom of Ben Sira, a book of maxims in the spirit of Proverbs of Solomon. Editions of the Vulgate usually include at the end of this book the Apocalypse of Ezra (another name is the second book of Ezra), a theological discussion of the fate of the people of Israel.

The large number of pseudepigrapha does not allow us to list them all here. The largest pseudepigrapha are the Book of Enoch (see Hanokh) and the Book of Jubilees. The first of these books is an eschatologically colored account of what was revealed to Enoch in heaven when "God took him" (Gen. 5:24), the second is a discourse on the predestination of all things, presented in the form of a conversation between an angel andMoses on Mount Sinai.

Of the smaller pseudepigrapha, the following are the best known: The Ascension of Isaiah— the story of the death of the prophet, also found in the Talmud; the book of the Assumption of Moses is a retrospective history of the Jews from the death of Moses to the death of Herod and his son; The Book of Adam and Eve, a narrative that deals with their fall from grace and Adam's death; The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the dying instructions given by each of Jacob's sons to his children. Although there are a number of Christian fragments in this book, most modern scholars regard the pseudepigrapha as Jewish with later Christian insertions. The book is an outstanding monument of Jewish epic literature.

We know of pseudo-epigraphs that have not reached us, associated with the names of Lamech, Abraham, Joseph, Eldad, Moses, Solomon, Elijah, Zechariah and others.

Tobit, Judith, additions Daniel, the Song of the Three Youths, and the Third Book of Ezra can be dated to the period of Persian domination (6th–5th centuries BCE), while the remaining apocrypha date to the Hellenistic period (4th–2nd centuries BCE). All the apocrypha share a concern for the fate of Israel as a whole, and they are all silent about sectarianism. Only after the emergence of sects at the beginning of the Hasmonean period did pseudepigrapha begin to appear. The Book of Jubilees was written during the reign of John Hyrcanus, the main part of the Book of Enoch appeared a little earlier, and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs a little later than the above-mentioned works. In any case, most of the pseudepigrapha known to us date back to the period between the reign of John Hyrcanus and the destruction of the Second Temple.

While the apocrypha is characterized mainly by the struggle against idolatry and the conviction that the period of prophecy had already ended (Judith 11:17), the authors of the pseudepigrapha believed that prophecy continued to exist and that through it they could make laws and know the past and the future. Since, however, the belief that the period of prophecy had ended was generally accepted, the authors of revelations and visions attributed their works to the ancients or declared themselves to be the people who were given to explain the true meaning of those passages of the Bible which, in their opinion, pointed to the "end of days". The period of the "end of days", according to the authors of the pseudepigrapha, was the time in which they lived.

Great importance in connection with this is attached in the pseudepigrapha to the question of the coming of the Messiah. The Essenes, among whom most of the pseudepigrapha may have originated, had many followers both in Eretz Israel and in the Diaspora. It was the exceptional attention the sect paid to these prophecies during the political crisis inThe period of Hyrcanus and the Roman procurators, forced the Pharisaic sages (see Pharisees) to erect a barrier between the Bible and all "external books," including such highly valued works as the Wisdom of Ben Sira (proof of its high value can be seen in the fact that it is the only apocrypha quoted in the Talmud).

«Susanna and the Elders». H. Ribera. Italian school. Late 17th century. Etching from the painting by S. Mulinari. Italy. 18th century.

«Susanna and the Elders». H. Ribera. Italian school. Late 17th century. Etching from the painting by S. Mulinari. Italy. 18th century.