Bible - Canon - Masora

MASORA (מָסוֹרָה, also מְסוֹרָה, mesorah, literally `tradition`), a set of instructions serving to preserve the canonized text of the Bible and the standards for its design when rewriting. In a narrower sense, it is an apparatus of notes that clarify the spelling, vocalization, syntactic division, stress, and cantillation of the biblical text, as well as cases of variant pronunciation of individual words.

The Talmud and medieval rabbinic literature call the Masorah a related term Masorete (Ps. 86b: Week 37b: Rashi to Deut. 33:23: Maim. Yad., Hilkhot Sefer Torah 8:4), which also meant the similar in meaning concept of `tradition`, but already Avraham Ibn Ezra used both terms. Both are usually derived from the root מסר (msr) — `to transmit` (according to some — also `to count`). However, the word masoreth (Ex. 20:37), which occurs once in the Bible, means `bonds`, from the root סר (ср) - `to bind`.

The importance of the Bible in the life of the Jewish people and the holiness attributed to it dictated the need to clarify its text, as well as to create rules for the technical design of the scrolls of the Holy Scripture. The text of the Pentateuch required particularly careful clarification, from individual words and even letters of which the decrees of the Oral Law were often extracted (see Hermeneutics; cf. Josephus, Apion 1:42). The verification of the text and the correction of errors and discrepancies that had entered the Bible copies that had been circulating since ancient times were carried out by sofrim, apparently from the beginning of the Second Temple period.

Tradition attributes Ezra (or the sophrim and the men of the Great council) corrections included in the canonized text, made primarily to avoid expressions inappropriate in relation to God. The Masorah counts 18 such corrections, which it calls either tikkunei sofrim (`corrections of the copyists`) or kinna ha-katuv (`Scripture has called`). In the canonized text of the Bible, from 800 to 1500 words have been preserved in their original spelling, according to various Masoretic lists, which it prescribes to replace when reading and designates them with the Aramaic terms krei (`read`) and aktiv (`written`). The earliest indications of this category, already found in the Talmud, include the constant replacement of the name of God Yahweh (see Tetragrammaton) when reading the biblical text with the name Adonai (Psach. 50a), and in some cases with the name Elohim, as well as the replacement of obscene words with euphemisms (Meg. 25b). Most of the krey and aktiv instructions concern the correction of spelling and grammatical errors, unusual or archaic letter combinations or vowels of words, and notes about extra or missing letters. A special group is formed by ten words that are pronounced but absent from the text (krei ve-la aktiv) and eight words that are present but omitted during reading (aktiv ve-la krei).

The critical remarks of the early sofrim were in the Talmudic era and were later supplemented by informative notes on discrepancies in the spelling of the same words found in the Bible in full (aktiv male) or incomplete form (aktiv khaser), with or without the connecting conjunction vav, with differences in vowel or stress. In each case, the number of such differences throughout the Bible was noted. The copyists also kept a count of the chapters, verses, words, and letters of each book of the Bible, indicating where these elements of the textand divide (according to the counting of each of them) the whole Bible and its separate books into equal parts (Kid. 30a). The Masorah also lists verses containing no more than three words, consisting of seven words with the letter yod in each of them, containing all the letters of the alphabet, three words of 11 letters each, etc.

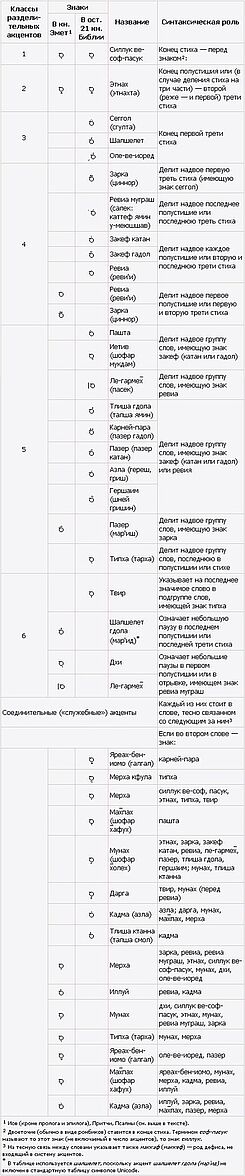

The schools of the Palestinian and Babylonian Masoretes (experts in the Masorah) that were formed at the early stage of the development of the Masorah are already mentioned in the Talmud (Kid. 30a). The fragments of Masoretic lists discovered in the Cairo Genizah reveal both a significant number of discrepancies between the indications of the Masoretes of Eretz Israel (ma‘aravaei — `western`) and Babylonia (medinhaei — `eastern`), and the existence of a school of Masoretes that arose in Tiberias in the 7th century, which developed the most complete system of the Masorah — the Tiberian one. The differences between the systems of these schools are particularly evident in the vocalization of the text (נִקּוּד— niqqud; see Writing) and in the placement of so-called accents (טְעָמִים — te'amim, טַעֲמֵי הַמִּקְרָא — ta'ameiха-микра), which play the role of punctuation, stress and cantillation marks in the Bible. In both the Palestinian and Babylonian Masorah (which had, in essence, two versions—Surah andHeharde‘i) these signs are placed only above words that require clarification of pronunciation; In the Tiberian Masorah, the entire text is vocalized, the vowel marks (with the exception of two) are placed under the letters, and most accents are either under or above the letters. The Tiberian Masorah, largely developed by five or six generations of Masoretes of the Ben Asher family, was in the 10th century. completed by Aharon Ben-Asher and practically displaced all other systems, including the developments of his opponent Moshe Ben-Naftali. See below tables 1, 2, 3.

The prohibition to introduce anything extraneous into the Bible scrolls intended for synagogue worship (Zeph. 3:7) led to the fact that for many centuries critical and informative notes of copyists, as well as the division into verses that was not graphically marked, as well as vowel marks and accents were transmitted orally or entered into special lists-guides. Only with the appearance in the 6th-7th centuries. handwritten Bibles, written on separate sheets, sewn into codices (mitzhafim), the information accumulated by many generations of Masoretes began to be entered into these copies, which were unsuitable for liturgical purposes. Lapidary, provided with a system of abbreviations and conventional signs, and using terminology borrowed mainly from the Aramaic language, the apparatus of notes and instructions of the Masoretes was reduced to the so-called small and large Masora, which differed mainly in the amount of information. The Lesser Masorah was usually written to the right or left of the text, less often between the lines, and is therefore also called the marginal or internal Masorah. The Greater or External Masorah was written above or below the text, and occasionally also to the side. Additional notes or their summary and the counting of various elements of the text (see above) were given in the Final Masorah, which was placed at the end of individual books of the Bible.

In many of these codices, the Masorah apparatus on the title and final leaves of the books of the Bible is inscribed in micrographic writing and is included in the ornamental decor of the leaf. The names of the copyist and the Masoretic copyist, as well as the date and place of completion of the work, were usually indicated in a special note - a colophon (the earliest - to the Book of Prophets with Masoretic notes by Moshe Ben-Asher. Tiberias, 894/95).

Masoretic material was also discovered in the Cairo Geniza, which does not follow the canonized order of the Bible text, butunited into separate thematic collections, such as, for example, the instructions cre and active, the rules for dividing the text into so-called open and closed passages, the rules for special lettering, a collection of discrepancies in parallel texts, etc. The largest collection of this kind is "Ohla ve-ohla" (before the 10th century), so named for the first pair (I Sam. 1:9 and Gen. 27:19) of an extensive list of hundreds of pairs of words that are identically and uniquely vowelized in the Bible, of which the second is used in combination with the prefix ve (the conjunction `and`). This work also contains about 400 notes (mainly from the large Masorah), listing the same words that differ in one letter, vowelization, stress, semantic meaning, etc. 80 lists of krei and ktiv, classified from various points of view, are given, and some other particulars of the Masorah from various periods and schools are listed.

At the end of the Masoretic period, a number of works appeared devoted to the relationship between the norms of the Masorah and the rules of grammar. The most significant work is considered to be the work of Aharon Ben-Asher "Sefer dikduqeha-te'amim" ("Book of the exact transmission of Masoretic signs", edition 1516/18), where, in addition to issues of the Masorah itself, the phonetic classifications of speech sounds, the pronunciation of shva, the rules for doubling certain consonants and excluding them, verb conjugation forms, etc. are discussed. Also well-known is the Arabic-language manual "Hidat al-kari" ("Instructions for the Reader"; it has many versions and translations, of which the most famous is the Hebrew translation "Horayat ha-kore", published in 1871).

The Aramaic translation of the Pentateuch, Targum Onkelos (see Onkelos and Aquila; Bible. Editions and translations). The Babylonian and Tiberian Masora, preserved only in rare copies, note some of its features, such as the translation of the same word of the Hebrew original into different Aramaic words, spelling and vowel differences introduced by the schools of Sura and Heharde‘i, etc.

The rules for the technical design of the biblical text and the production of the Torah scrolls are found in various treatises of the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds. Collected in the so-called minor tractates Massekhet Sefer Torah and Massekhet Sofrim, they prescribe: the form and limits of the size of the font; unusual (enlarged, reduced, or "suspended") outline of certain letters; placing dots above or below certain letters or words (the meaning of all these elements is unclear); the ratio of the width of lines to the height of columns; the size of the intervals between letters, words, lines, chapters, and columns; a special breakdown of the text of biblical hymns of praise (latitudes; Ex. 15, Deut. 32, Judges 5, II Sam. 22, Psalm 18), etc. The rules for writing the names of God in their proper and common meanings are set out in detail (see God. Names; God. In the Bible. Names). The instructions for making scrolls determine the material suitable for this, the composition of the ink, the method of ruling and sewing the strips of parchment, the qualifications required of the scribe (for more details, see Torah). It is considered mandatory to copy the text from a carefully checked original.

Since the 13th century, works have appeared that summarize the accumulated material and contain its critical analysis and attempts to compile an authoritative guide to the Masor. Some of them are also devoted to the study of the history of the Masorah.

One of the first to make a significant contribution to this area was Yekuthiel ben Yehuda ha-Nakdan (early 13th century), the author of the book "Ein ha-kore" ("The Reader's Eye"), which became the main manual on the vocalization and grammar of the biblical text. Meir ben Todros ha-Levi Abul'afia (170?–1244) wrote Masoret siag la-Torah (Masora—the enclosure of the Torah, published in 1730), the rules of which long guided editors of manuscript and printed editions of the Bible. Menachem Meiri set out in his work "Kiryat Sefer" ("City of the Book", 1306, published 1863–81) the rules for copying the scrolls of the Torah and the grammatical clarifications of its reading. Yaakov ben Chaim ibn Adonijah (1470?–1535?), preparing the 2nd edition of Daniel Bomberg's "Mikraot Gdolot" (1524/25), the biblical text of which he sought to provide with the most accurate collection of Masoretic notes, collated a large number of Masoretic manuscripts. Despite its major shortcomings, this edition was considered exemplary in its time. E. Levita's Masoret ha-masoret (The Tradition of the Masorah, 1538) became the fundamental study of the history of the development of the Masorah. Menachem ben Yehuda di Lonzano (1550—before 1624), having limited his work Or Torah (The Light of the Torah, 1618) to notes on the Pentateuch, refined the spelling, vocalization, and accentuation based on the works of a number of Masoretes. text. Yedidia Shlomo Norzi (1560–1616) was the definitive authority on the Masoretic apparatus of the Bible, and his work Minchat Shai (The Offering of the Gift, 1742–44) was the most important guide to Masoric matters. For Yemenite Jews, equally authoritative was the work of Ihye ben Joseph Salih (c. 1715–1805) Helek (or Halluk) ha-dikduk (The Smooth Stone of Grammar, 1885) on vocalization, accentuation, and some problems of the grammar of the Pentateuch. A turning point in the interpretation of the material of the Masorah was the work of the grammarian and Bible commentator B. Z. Heidenheim (1757–1832), who included in the Masoretic apparatus of five separate editions of the Pentateuch (1797–1818) the instructions of Jekuthiel ben Yehuda ha-Nakdan, M. di Lonzano, I. Sh. Norzi and a number of other Masoretes, printed under his supervision, as well as his own notes based on a systematic review of the problems of the Masorah. Of great importance is also his work “Mishpetei ha-te‘amim" ("Rules of Masoretic Accents", 1808) with detailed standards for the system of accents in the remaining books of the Bible.

Heidenheim's student Z. I. Behr (1825–97) re-edited the entire Masoretic apparatus for the publication of the Bible (1869–95), including the prophetic and hagiographical books, which had not been published by his predecessor. In his work "Torat Emet" ("Teaching of Truth", 1853), built according to the plan of "Mishpetei ha-te‘amim", Behr sets out the rules for placing accents in the books of Job, Proverbs and Psalms (the so-called Book of Emet, an abbreviation of the Hebrew title of these books), where the rules of accentuation are different from those in the other (21) books of the Bible. Unlike Heidenheim, he does not always rely on other scholars, but is often guided by the system of Masorah rules he developed and sometimes generalizes indications that were not sufficiently confirmed by the works of previous Masoretes. Nevertheless, the edition of the Bible edited by Behr was considered exemplary for a long time.

The biblical scholar, baptized Jew K. D. Ginzburg (1831–1914) compiled Masoretic material from the dozens of manuscripts (including very rare ones), arranged it in alphabetical order, provided glosses and supplemented it with a reprint of a number of individual works on the Masorah. The two editions of the Bible edited by Ginzburg (1894, 1911) are based on the rules developed in this work, although they are far from always scientifically substantiated. In the book "Introduction to the Masoretic-Critical Edition of the Bible" (in English, 1897) Ginzburg gives a general overview of the history of the development of the Masorah, examines its main tasks and terminology and provides a description of many manuscripts of the Bible.

The main works of the German Hebraist P. E. Kale are devoted mainly to the study of fragments of the Masorah discovered in the Cairo Geniza. In his works The Masoretes of the East (1913) and The Masoretes of the West (1927–30), Kahle showed how the independent systems of vocalization of the biblical text developed in the Babylonian and Palestinian centers of Jewish scholarship subsequently merged into the Tiberian system, which received its final form in the school of Aharon Ben-Asher.

Significant contributions to the study of the origins of the Masorah and to the publication of the text of the earliest manuscripts of the Bible were made by scholars from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem andTel Aviv University. Professor A. Dotan (born in 1928) in the works “Sefer Dikduqei Ha-Te‘amim Le-Rabbi Aharon ben Moshe Ben-Asher” (see above; 1967) and “Ozar Ha-Masora Ha-Tveryanit” (“Dictionary of the Tiberian Masorah”, 1977) analyzes in detail the Masoretic tradition of the Ben-Asher school. The edition of the Bible edited by him (1973) reproduces the earliest complete text with the Masoretic apparatus that has come down to us, the so-called Second Leningrad Bible, rewritten in 1008–1010 from the manuscript of Aharon Ben-Asher (kept in the M. Saltykov-Shchedrin Library, St. Petersburg). In 1975, Dotan published an English translation of the work "Ha-masorah" by K. D. Ginzburg, providing it with an extensive introduction and critical analysis. He also wrote an extensive general article, "Masora," in the Encyclopedia Judaica (in English, Yer., 1971).

Professor I. Yeivin (1923–2008) studied the issues of vocalization and the accent system of the earlier, but only partially preserved, so-called Aleppo Codex (dated 929, kept at the Yad Ben-Zvi Institute, Jerusalem) in his works "Keter Aram-Tsova, nikkudo ve-te'amav" ("The Aleppo Codex, Its Vowelization and Accentuation," 1969) and in "Mavo la-masora ha-tveryanit" ("Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah", 1972). In his edited "Osef kit'ei ha-gniza shel ha-mikra be-nikkud u-ve-masora bavlit" ("Collection of Bible fragments from the Geniza with Babylonian vocalization and the Masorah", 1973) he examines the characteristics of the Babylonian school. For the Encyclopedia Mikrait (Yer., 1968) he wrote a review article, "Masora."

The linguist and lexicographer Professor M. Goshen-Gottstein (1925–91) touches upon the issues of the Masora of the Tiberias school in the article "Ha-otentiut shel Keter-Halab" ("The Authenticity of the Aleppo Codex") for the collection "Mekhkarim be-Keter Aram-Tzova" ("Research on the Aleppo Codex," 1960; editor H. M. Rabin). The history of the development of the Masorah is also the subject of his book, The Origin of the Tiberian Text of the Bible (in English, 1963).

An accent, if it is the only one in a word, is placed on the stressed syllable. If there are two accents in a word, the second one is placed on the stressed syllable.

It must be assumed that the silluk sign (see the beginning of the table) was especially associated with stress marking. The sign meteg or ga‘ya, which is written in the same way, denotes an additional (weaker) stress (preceding the main stress) in three-syllable and longer words.

(ס conventionally represents the letter in general here).

| סּ | Dagesh | Strengthening a consonant: a) doubling it b) in the letters ת, פ, כ, ד, ג, ב— preserving the occlusive character¹ |

| הּ | Mappik | Consonantal character of the letter ה at the end of a word |

| סֿ | Rafe | Weakening of a consonant (the sign opposite to dagesh or mappik); was used less frequently than other characters |

| Reading the letter ש respectively as: | ||

| שׁ שׂ | sh (sin) or s (sin) | |

| ¹ In modern Hebrew it is only significant for פ,כ,ב. Doubling is only possible after a vowel: if dagesh is in the letters ת, פ, כ, ד, ג, ב after a vowel: it performs both functions at once. See also Alphabet. | ||

| Sign | Name | Sound | |

|---|---|---|---|

| סִי,סִ | hirik | i¹ | |

| סֵי, סֵ | cere | e private | |

| סֶ | segol | e open | |

| סַ | pattah | a | |

| סָ | kamats | #596; (sound between a and o)² | |

| סֹ,סוֹ | holam | o | |

| סֻ | kubbutz | u | |

| סוּ | shuruk | ||

| סְ | шва | шва на | fluent indefinite vowel (like ə³) |

| шва нах | absence of a vowel | ||

| סֲ | hataf-pattah | fluent a | |

| סֱ | hataf-segol | fluent e | |

| סֳ | hataf-kamats | fluent ɔ4 | |

| ¹ Short or long [i]. The length of a vowel is often indicated by the presence in the text (even before the Masorah) of the so-called immot ha-kriya (`mothers of reading`), i.e. the letters ה, א, ו, י in the case of their loss of consonant sound; but without them the vowel can be long. ² In the Sephardic tradition it represents two sounds: kamatz gadol— [a], kamatz katan— [o]. ³ Later merged with [e]. 4 In the Sephardic tradition, it is a fluent [o] (see note ²). | |||

| Classes of Separating Accents | Signs | Title | Syntactic Role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the Book of Emeth¹ | In the Remaining 21 Books of the Bible Bible | |||

| 1 | סֽ | סֽ | Silluk ve-sof-pasuk | The end of the verse - before the sign׃² |

| 2 | ס֑ | ס֑ | Etnakh (etnakhta) | End of hemistich or (in case of dividing the verse into three parts)—the second (less often—and first) third of the verse |

| 3 | ס֒ | Seggol (sgulta) | End of first third of verse | |

| ס֓ | Shalshelet | |||

| ס֥֫ | Ole-ve-iored | |||

| 4 | ס֘ | Zarka (tsinnor) | Divides the first third of the verse (which has the seggol sign) in two | |

| ס֜֗ | Revia mugrash (saleq: kattef yamin u-meyushshav) | Divides the last hemistich or the last third of the verse in half | ||

| ס֔ | Zakef katan | Divides each hemistich or the second and last thirds of the verse in half | ||

| ס֕ | Zakef gadol | |||

| ס֗ | Reviation (revi‘i) | |||

| ס֗ | Revi‘i (revi‘i) | Divides the first hemistich or the first and second thirds of the verse in two | ||

| ס֘ | Zarka (tsinnor) | |||

| 5 | ס֙ | Pashta | Divides a group of words with the sign zaqef (katan or gadol) in two | |

| ס֚ | Yetiv (shofar mukdam) | |||

| ס׀ | Le-garmekh (pasek) | Divides a group of words with the revia sign in two | ||

| ס֠ | Tlisha gdola (talsha yamin) | Divides a group of words that have the sign zaqef (katan or gadol) or revia in two | ||

| ס֟ | Karnei-para (pazer gadol) | |||

| ס֡ | Pazer (pazer katan) | |||

| ס֜ | Azla (geresh, Grisha) | |||

| ס֞ | Gershaim (Schney Grishin) | |||

| ס֡ | Pazer (mar‘ish) | Divides a group of words with the zarka sign in two | ||

| ס֖ | Tipkha (tarkha) | Divides a group of words, the last in a half-verse or verse | ||

| 6 | ס֛ | Twir | Indicates the last significant word in a subgroup of words that has the tipha sign | |

| ס֓ | Shalshelet gdola (mar‘id)* | Indicates a small pause in the last phemiverse or last third of the verse | ||

| ס֭ | Dhi | Denotes small pauses in the first hemistich or in a passage marked with the revia mugrash sign | ||

| ס׀ | Le-garmekh | |||

| Connecting ("service") accents | Each of them is in a word closely related to the one following it ³ | |||

| If the second word contains a sign: | ||||

| ס֪ | Yareah-ben-yomo (galgal) | karnei-para | ||

| ס֦ | Merha kfula | tipha | ||

| ס֥ | Mercha | silluk ve-sof, pasuk, etnakh, tipkha, tvir | ||

| ס֤ | Makhpakh (shofar khafukh) | pasta | ||

| ס֣ | Munach (shofar kholekh) | etnah, zarqa, zakef katan, revia, le-garmex, paeer, tlisha gdola, gershaim; munah, tlisha ktanna | ||

| ס֧ | Darga | tvir, munah (before revia) | ||

| ס֨ | Kadma (azla) | azla; darga, munakh, makhpakh, merha | ||

| ס֩ | Tlisha ktanna (talsha smol) | kadma | ||

| ס֥ | Merha | zarka, revia, revia mugrash, etnakh, silluk ve-sof-pasuk, munakh, dhi, ole-ve-iored | ||

| ס֬ | Illui | revia, kadma | ||

| ס֣ | Munakh | dhi, silluk ve-sof-pasuk, etnakh, munakh, revia mugrash, zarka | ||

| ס֖ | Tipkha (tarkha) | munakh, merkha | ||

| ס֪ | Yareakh-ben-yomo (galgal) | ole-ve-iored, pazer | ||

| ס֤ | Mahpah (shofar hafuh) | yareah-ben-yomo, munah, mercha, kadma, revia, illui | ||

| ס֨ | Kadma (azla) | illui, zarka, revia, maхпах, pazer, merkha | ||

| ¹ Job (except for the prologue and epilogue), Proverbs, Psalms (see above in the text). ² A colon (usually in the form of a diamond) is placed at the end of a verse. The term sof-pasuk is used to refer either to this sign (not included in the number of accents) or to the silluk sign. ³ The close connection between the words is also indicated by makkaf (makkef), a kind of hyphen that is not included in the accent system. * The table uses shalshelet, since the accent shalshelet gdolah (mar‘id) is not included in the standard Unicode character table. | ||||

Masoretic Accents (Te'amim)

Masoretic Accents (Te'amim)